We often talk about device alerts and device design in terms of productivity, convenience, and connection. We talk about screen time, social media, and distraction. But far less attention is paid to something deeper and more fundamental: how the modern sensory environment created by our devices interacts with the human mind and body directly.

Phones, computers, TVs, smartwatches, alarms, and screens do not just deliver information. They emit signals — sounds, lights, vibrations, colors, and patterns — that continuously communicate urgency, availability, and demand. These signals are processed by nervous systems that evolved for a very different environment. The result is not just distraction, but a persistent state of low-grade alertness that affects sleep, mood, attention, and mental health.

Here we examine how device alerts, sound design, notification systems, vibration, light, color, and interface choices quietly keep us keyed up — and what that means for our bodies and minds.

We Are Not Just Overstimulated — We Are Over-Alerted By Device Alerts

A useful shift in perspective is to stop thinking in terms of “stimulation” and start thinking in terms of alert signaling.

Human nervous systems evolved to detect changes in the environment that might signal danger, opportunity, or social demand. Sudden sounds, flashes of light, movement in the periphery, and tactile sensations all activate ancient neural pathways responsible for vigilance and orientation.

Modern devices replicate these cues constantly.

Device alerts: Notifications, pings, badges, vibrations, and screen flashes are not neutral. They are engineered interruptions, designed to cut through whatever else we are doing and redirect attention. Even when they are not consciously stressful, they increase physiological arousal.

Research on stress physiology shows that repeated activation of the sympathetic nervous system — even in small bursts — contributes to cumulative stress load, known as allostatic load, which is associated with anxiety, sleep disruption, impaired concentration, and emotional dysregulation over time (National Institute of Mental Health).

In other words, it’s not just what we see or hear — it’s what our nervous system is repeatedly told: stay ready.

Sound Design and the Nervous System

Sound is one of the most powerful alert mechanisms we have. Unlike visual input, which we can sometimes ignore, sound demands attention automatically. The brain processes auditory stimuli rapidly, engaging alertness circuits in the brainstem before conscious interpretation occurs.

Most notification device alerts and alarm sounds are designed with:

- Fast attack (they start abruptly)

- High frequencies

- Repetition

- Sharp transients

These characteristics are effective because they mimic environmental sounds that historically signaled danger or urgency. Even when we cognitively recognize a sound as “just a notification,” the nervous system reacts first.

Alarm clocks are a clear example. Traditional digital alarms are intentionally jarring, designed to forcibly pull the brain out of sleep. But sleep research shows that abrupt awakenings can spike cortisol levels and increase sleep inertia — the groggy, disoriented feeling after waking (Sleep Foundation).

More gradual wake-up cues — such as slowly increasing light or sound — are associated with gentler transitions between sleep stages and more stable alertness. Yet abrupt alarms remain the default, largely because reliability and urgency have been prioritized over physiological comfort.

Vibrate Mode: Silent, But Not Calm

Many people switch their phones to vibrate in an attempt to reduce noise and stress, to themselves as well as anyone else nearby. But vibration does not remove alerting — it moves it into the body.

Haptic alerts activate somatosensory pathways directly. The sensation is felt, not just heard or seen. Over time, this creates strong conditioning between bodily sensation and anticipation of demand.

This conditioning can become so ingrained that people experience phantom vibration syndrome — the sensation that a phone is vibrating when it is not. A study published in The BMJ documented how common this phenomenon is among frequent phone users, highlighting how deeply conditioned the nervous system can become to haptic alerts (BMJ).

Vibration is often perceived as a “gentler” alternative to sound for device alerts, but neurologically it is not neutral. It keeps part of the body in a state of readiness, especially when the device is carried on the body throughout the day.

Visual Alertness: Light, Color, and Motion

Screens are not just information displays — they are light-emitting sensory environments.

Blue-weighted light from screens suppresses melatonin production, delaying sleep onset and shifting circadian rhythms (Sleep Foundation). This is why night modes and warm color filters exist. But light color is only one part of the story.

Interface design also relies heavily on:

- Bright contrast

- Saturated colors

- Red notification badges

- Movement and animation

- Unread indicators

These elements are designed to increase salience. Our visual systems evolved to notice contrast and motion because they once signaled predators, prey, or environmental change. Digital interfaces hijack this system.

A flashing badge or unread count may seem trivial, but it acts as a persistent unresolved signal, telling the brain that something requires attention. Research on notifications and attention shows that even the presence of unread indicators can increase anxiety and reduce task focus, even when users do not interact with them (arXiv).

This is why grayscale mode can be effective. Removing color reduces emotional salience and dampens the urgency encoded in visual cues. It doesn’t eliminate functionality — it reduces nervous system activation.

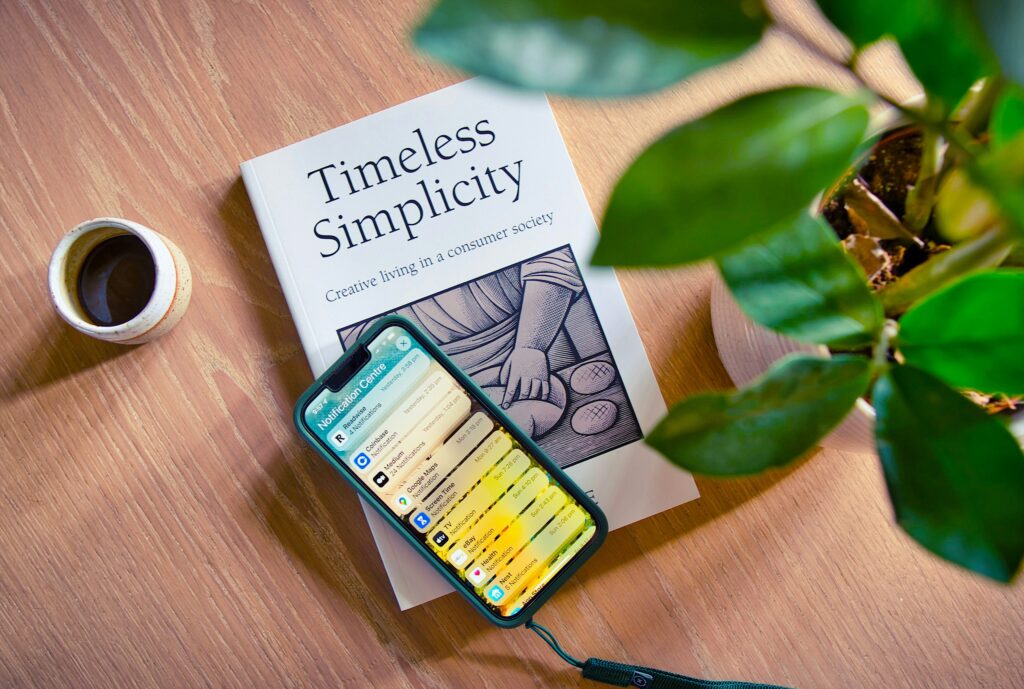

The Illusion of Control: Do Not Disturb and Managed Vigilance

“Do Not Disturb” modes are often framed as solutions to digital overload. But they frequently offer the illusion of disconnection without actual absence of device alerts.

Many DND settings still allow:

- Visual notifications

- Exceptions for certain contacts

- Emergency bypasses

- Persistent badges

- The physical presence of the device nearby

From a nervous system perspective, this creates managed vigilance rather than rest. The body remains partially alert because the possibility of the an interruption from device alerts still exists.

Sleep research suggests that the mere presence of potential alerts can fragment sleep architecture, even if alerts do not occur. A review of studies on electronic device use and sleep found that proximity to devices is associated with poorer sleep quality and increased nighttime arousal (PubMed Central).

True rest requires not just silencing signals, but removing the expectation of signaling.

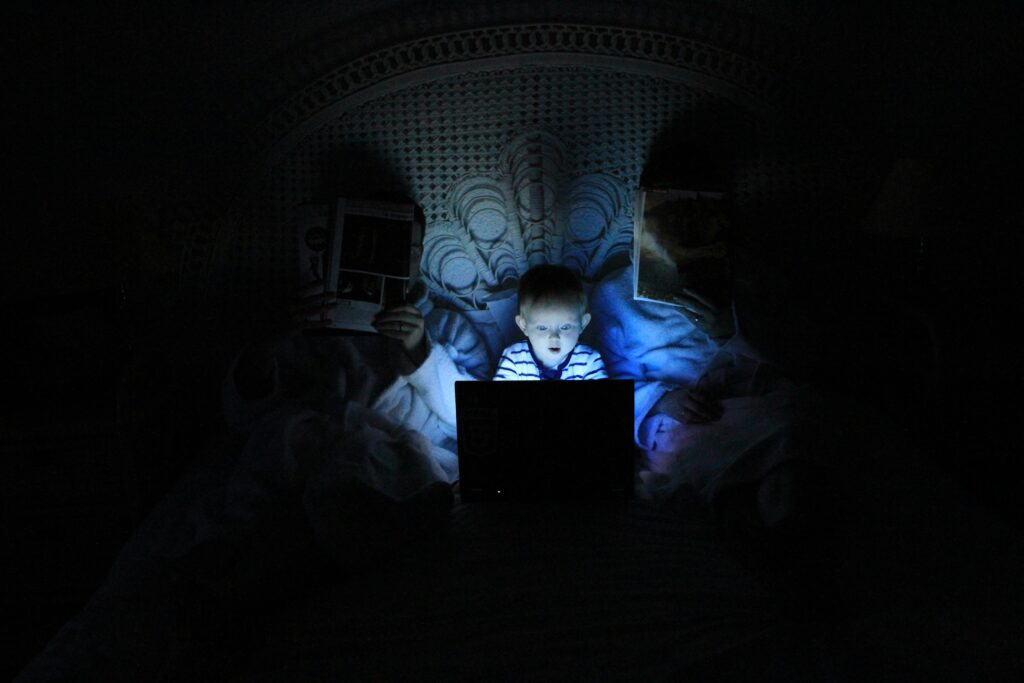

Sleep, Anticipation, and the Cost of Sudden Alerts

Sleep is not a passive state. The brain cycles through stages that rely on predictability and safety. Sudden sounds or light changes disrupt these cycles, but so does anticipation of disruption.

Sleeping next to a phone that might ring, buzz, or light up keeps part of the nervous system semi-engaged. This contributes to:

- Lighter sleep

- More frequent micro-awakenings

- Difficulty returning to sleep

- Feeling tired despite adequate sleep duration

Articles summarizing sleep research consistently link nighttime screen exposure and alerting devices to fragmented sleep and emotional dysregulation (AP News).

Using phones as alarm clocks intensifies this problem because the device is both a sleep disruptor and a communication portal. Stand-alone alarm clocks, particularly those using gradual light or sound, remove that layer of anticipatory stress.

Why We Stay Connected Even When It Hurts

Many people recognize that their devices contribute to stress, yet still feel compelled to keep them close. This is not a failure of willpower — it’s a result of intermittent reinforcement.

Notifications arrive unpredictably. Sometimes they carry important or rewarding information. Sometimes they don’t. This unpredictability keeps the nervous system alert, scanning for the next signal.

Research on notification silencing has even shown that turning notifications off can temporarily increase stress and checking behavior, because users fear missing something important (UPI).

This highlights an uncomfortable truth: many people are not addicted to content, but to availability. The obligation to be reachable keeps the nervous system engaged, even when there is nothing to respond to.

Practical Ways to Reduce Sensory Load Without Disconnecting Completely

The goal is not to eliminate technology, but to reduce unnecessary alerting and restore nervous system balance.

Rework sound and haptics

- Use softer, lower-frequency notification tones

- Disable vibration unless essential

- Avoid sharp, repetitive alarm sounds

Reduce visual urgency

- Turn off badge counts and unread indicators where possible

- Use grayscale mode and/or “bedtime” mode at least 30 minutes before sleep

- Minimize animations and motion where possible

Make rest real

- Keep phones out of the bedroom at night

- Use a separate alarm clock – consider light based alarm clock for a more natural alarm (https://amzn.to/45w2uhh) (we don’t “love” Amazon, but we know it’s one of the cheapest ways to buy a product like this, full disclosure this is also an affiliate link. Please feel free to buy this product elsewhere, or not at all)

- Charge devices outside sleeping spaces

Control light exposure

- Use warm lighting in the evening

- Avoid bright screens before bed

- Enable dark modes and night filters consistently

Batch communication

- Check messages at designated times instead of responding to every alert

- Remove push notifications for non-critical apps

- Unsubscribe from unwanted emails

- Reply “Stop” or block spam text messages

- Uninstall unused apps

These changes reduce intermittent alerting, which is one of the biggest drivers of nervous system fatigue.

Calm Is Not Silence — It Is Safety

Calm is not the absence of sound or light. It is the presence of predictability and safety. A nervous system at rest is not one that receives no signals, but one that receives signals that are gentle, consistent, and non-urgent.

Modern devices were designed to capture attention, not to support regulation. Understanding this allows us to stop blaming ourselves for feeling overwhelmed and start redesigning our environments in ways that align with human biology.

In a world saturated with alerts, choosing calm becomes a design decision — not a personal failure.

Check Out Related Categories on Interconnected Earth

- Mental Health: https://interconnectedearth.com/mental-health

- Technology: https://interconnectedearth.com/technology

- Philosophy: https://interconnectedearth.com/philosophy